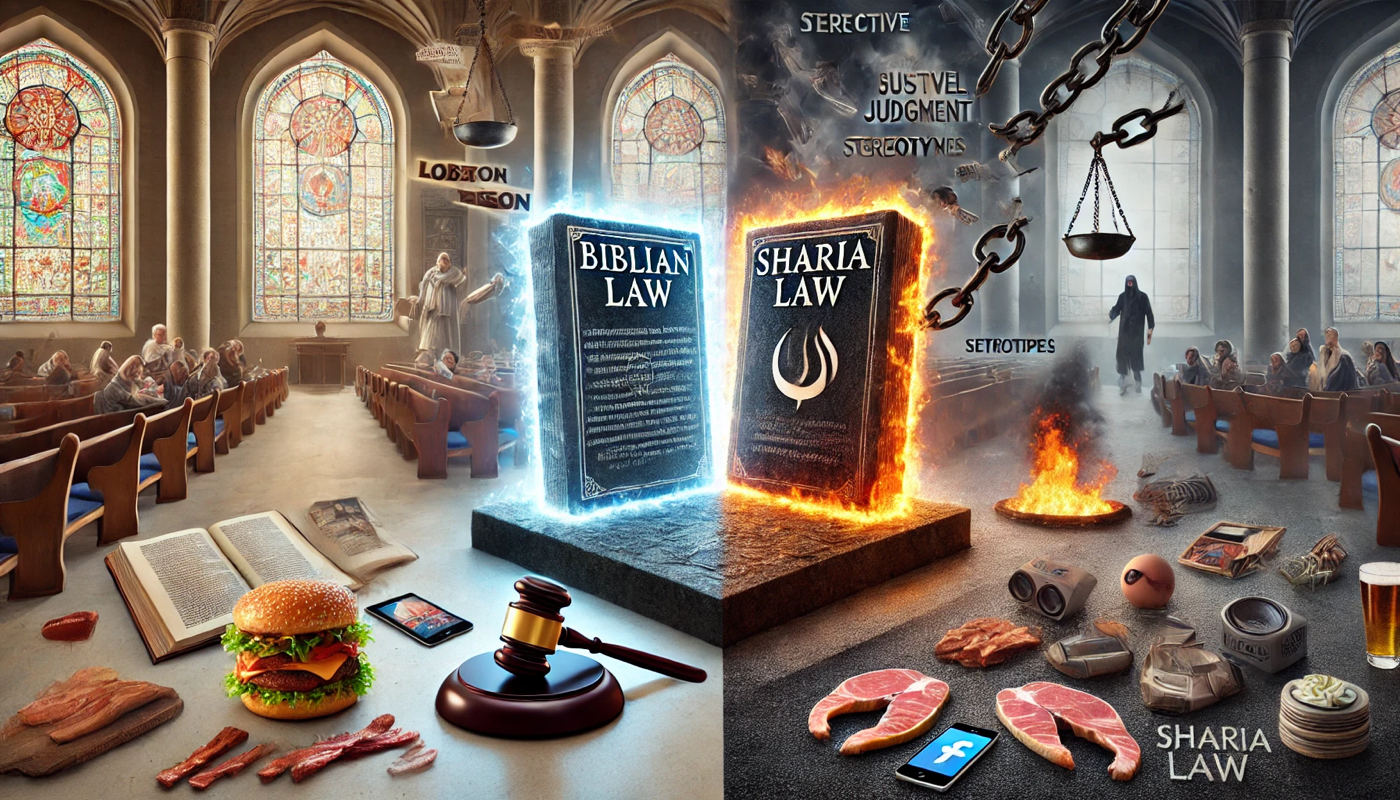

Ask the average Westerner about Sharia law, and you’d think they were recounting the script of a medieval horror show: public stonings, amputations for theft, and women living in perpetual fear of a headscarf gone askew. Now, ask them about biblical law, and the mood suddenly shifts. Expect vague nods to the Ten Commandments, some inspirational Pinterest quotes about “loving thy neighbor,” and maybe a soft-focus image of Charlton Heston descending from Mount Sinai. But here’s the kicker: many of the things Westerners fear most about Sharia—strict moral codes, harsh punishments, and divine decrees—are right there in the Bible, too.

Most Christians treat the Old Testament like the fine print on a credit card agreement. Sure, it’s technically there, but does anyone actually read it? Hidden among the Psalms and Proverbs is a legal system that makes Sharia look like a team-building seminar. Stoning for adultery? Classic Old Testament. Working on the Sabbath? Death penalty. Disobeying your parents? Yep, that’s another stoning. Even dietary laws are strict enough to ruin a church potluck—no pork, no shellfish, and absolutely no bacon-wrapped shrimp. Yet modern Christians have hit the “mute” button on these rules, thanks to a theological plot twist: Jesus came, died, and now you can eat bacon guilt-free.

This convenient amnesia about biblical law isn’t just theological; it’s cultural. Christians cherry-pick the parts of the Bible that fit their modern worldview while ignoring the harsher stuff, like the whole “stone your rebellious son” clause. But when it comes to Sharia? Suddenly, every rule is gospel, every punishment literal, and every adherent an extremist.

Meanwhile, Sharia law has been turned into the boogeyman of Western imagination. To hear some people tell it, Sharia isn’t just a legal system—it’s a sinister plot to take over the world, one headscarf at a time. Yes, Sharia prescribes harsh punishments—amputation for theft, flogging for adultery—but, like biblical law, these come with a web of conditions, exceptions, and a healthy dose of mercy. The trouble is, nuance doesn’t sell headlines. Instead, Sharia becomes shorthand for “barbaric,” a convenient scapegoat for fears about Islam and, by extension, non-Western cultures.

The truth is, most Muslims don’t live under strict Sharia law. Its interpretation varies wildly, from personal practices like prayer and charity to full legal systems in certain countries. But nuance is rarely the point. Sharia has become a symbol of “the other,” a stand-in for Middle Eastern, South Asian, or African identities that don’t fit neatly into Western norms. Criticizing Sharia isn’t just about laws—it’s about fear. It’s Islamophobia with a Bible in hand.

And that Bible? It’s got plenty in common with Sharia. Both systems emerged in patriarchal, agrarian societies where maintaining order meant strict codes of conduct. Both prescribe harsh punishments for offenses like theft, adultery, and blasphemy. And both, crucially, emphasize mercy and redemption. Take repentance, for example. The Quran states that a thief who repents and reforms should be forgiven, just as the Bible is full of second chances—like King David’s redemption after adultery or Jonah sparing Nineveh after a divine guilt trip.

So why does Sharia get the villain edit while biblical law enjoys its retirement as a cultural relic? Familiarity is part of it. Biblical law is woven into the cultural wallpaper of the West, a set of moral guidelines more associated with “Thou shalt not kill” than “Thou shalt not wear polyester blends.” Sharia, on the other hand, feels foreign, mysterious, and threatening. It’s easier to demonize something you don’t understand.

But the selective criticism of Sharia isn’t just hypocritical—it’s dangerous. By focusing on the harshest elements of Islamic tradition while ignoring similar aspects of biblical law, the West reinforces a false dichotomy: the idea that “our religion” is inherently enlightened while “theirs” is primitive. This narrative deepens divides, fuels fear, and perpetuates stereotypes that hurt everyone involved.

The real kicker is that neither biblical law nor Sharia is inherently better or worse. Both reflect the values of their time, and both require thoughtful, modern interpretation to stay relevant. The problem isn’t the laws themselves—it’s the way we use them to justify fear, prejudice, and moral superiority.

So before we cast stones at Sharia law, maybe it’s time to look at the stones we’ve conveniently hidden in our own backyard. After all, the Bible’s got its fair share of shellfish bans, stoning mandates, and other rules that wouldn’t fly at your average Sunday school. The real question isn’t whether biblical law is “better” than Sharia—it’s why we’re so eager to forget one while demonizing the other. Perhaps, in the end, the only thing more outdated than these ancient laws is the selective fear we choose to project onto them.